Visual Artifact Page

Atlanta ROlling Mill

In 1858, the Atlanta Rolling Mill was constructed on a rural plot of land east of downtown. When it opened, it was one of the few factories in the South that could produce iron rail—the key ingredient to connecting American cities and fueling the nation's expansion into new territories.

During the Civil War, however, the Atlanta Rolling Mill became the Confederate Rolling Mill as the factory’s output shifted towards the growing needs of the Confederacy. During that time, it produced iron rail, cannons, and sheets of iron cladding for the ships of the Confederate navy.

Lt. Gen’l John Bell Hood (1831 - 1879)

General Hood was a lieutenant general for the seceding Confederacy. On September 1, 1864 he gave orders to destroy the Confederate Rolling Mill so that it would not fall into the hands of the Union.

Confederate Rolling mill destroyed

On the night of September 1, 1864, Confederate troops set fire to several trains idling next to the Confederate rolling mill. The boxcars—loaded down with munitions—detonated, destroying the mill and everything around it for a quarter mile. The above image shows the aftermath.

16 years later, Jacob Elsas would purchase this battle-scarred tract of land and construct the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill in its place.

General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820 - 1891)

Union General Sherman, pictured above, overlooking the battlefield during the Atlanta campaign. In November of 1864, he ordered the evacuation of Atlanta in order to mitigate the loss of life during the burning that Sherman would eventually order. When the mayor and city council appealed for mercy, he replied,

“…The use of Atlanta for warlike purposes is inconsistent with its character as a home for families. …

You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.”

You can read his full statement here.

american forces destroying rail lines

Before burning and leaving Atlanta, Union troops destroyed as many rail lines as possible. The goal was to cripple the city and prevent it from supplying Confederate forces in the future.

Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill

This image, taken from the vantage point of Decatur Street, was shot during the labor strike of 1914. The exterior mill looks mostly the same today (sans the central smokestack and the furthest-left tower in the photo). The rail line in the foreground is still active.

OScar Elsas

President of the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill. As pictured around the time of the strike.

Offices - fulton bag & cotton mill

Oscar Elsas employed the largest office staff of any mill in the south. In the recesses of this office is where the Vault was located.

the strike begins

The Atlanta Constitution ran this short story on May 21, 1914, the morning after the strike began.

List of strikers

This hand-written list of strikers was found inside a ledger, recovered inside the mill’s vault.

list of strikers

A sample of the list of strikers who walked off the job when the strike began on May 20, 1914.

elsas responds

Oscar Elsas commissioned this response for the June 3rd edition of the Atlanta Constitution. The next day, evictions began.

ola “delight” smith

As a resident of Atlanta with a long history of labor activism, Ola Delight Smith was a natural fit as a leader of the Fulton Bag strike. Shortly after the strike began, she joined Charles Miles as the strike’s second leader.

Smith harnessed the power of photography and film to broadcast the stories of the strikers with the goal of garnering sympathy for their cause.

Smith was known for her boldness and moxy. Historian Gary Fink once described her as “a human whirlwind of action.”

child laborers

Smith photographed these four boys—all workers in the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill—and hand-wrote their weekly wages at the bottom of the photo.

rallies begin

Before the strike even began, labor activists began holding rallies at the newly constructed Odd Fellows Temple.

odd fellows temple

The Odd Fellows Temple (shown today at left, and, at right, when it was built in 1913) was the site of daily strike meetings throughout the summer of 1914.

dictograph rental

In June of 1914, Oscar Elsas rented a dictograph from the Railway Audit & Inspection Company which provided espionage equipment and agents to corporations.

The dictograph was a primitive eavesdropping device.

dictograph report

Elsas ordered two of his operatives to install the dictograph in the ceiling of the Odd Fellows building. Once functioning, those operatives could listen in on the union’s plans. The above report was submitted to Elsas by “Operative A.E.W.”.

spy report

Newly hired Operative #115 reports on his first day on the job. In his attempts to infiltrate the union, he “posed as an Englishman coming from Philadelphia.”

Spy report

Another daily report from Operative #115.

ola’s scrapbook

Ola Delight Smith made a large scrapbook, documenting life during the strike. Each page included an image and her hand-written captions beneath them.

The image above shows three of the union leaders standing in front of the Union commissary (note the Coca-Cola advertising).

Smith displays a dramatic, dour expression, likely with the goal of visually emoting the sad and miserable life of those living in the mill village. Fellow strike leader, Charles Miles, is to her right in the photo.

strikers at the commissary

A large group of strikers pose in front of the union commissary. Leaders Ola Delight Smith and Charles Miles are standing in front of the group, at center.

Smith often staged large group photos like this as a way to display the large number of workers who’d joined their efforts.

the commissary

The commissary, representing the local chapter 886 of the United Textile Workers of America, was set up right in the shadow of the cotton mill. Striking workers could get free food and provisions from the commissary, funded by the national UTW and through local donations.

Tennelle Street today

This photo was taken 105 years after the strike, from roughly the same vantage point as the preceding photo. Note that the rust-colored house on the left is barely visible in the previous photo (at center, tucked behind the commissary sign).

You can also see that the original concrete wall surrounding the mill is still there today. The wall now acts as a canvas for a community art project called Stacks Squares.

strikers on parade

The strikers would often take their pickets to the streets, marching through Atlanta’s busiest thoroughfares with the goal of spreading the word and gaining support for strike efforts.

“let us have justice” tee

The design inspiration of our Let us Have Justice tees came from an old photo of a sign, held by one of the strikers during the Fulton strike of 1914 (shown at bottom right).

Inside the Catlick store, you’ll see a variety of LUHJ items including two tees, a print, and a sticker. Shop the collection and use 19NOW to save 19% off any t-shirt.

evictions begin

On June 4, 1914, Oscar Elsas ordered his private security force to begin evicting striking families from company housing. Men on horseback forcibly entered homes and began piling personal belongings in the street. This image was taken from the southern end of present-day Carroll Street, directly across from Carroll Street Cafe.

Click here for a virtual tour of Carroll Street today.

striker/actress, margaret dempsey

Margaret Dempsey was a 54-year old widowed striker. On the day of evictions, Dempsey and her young son were evicted from their home on Carroll Street. In this photo, Dempsey is shown with her hands thrown into the air—an exasperated and distraught pose. She stands beneath Ola Smith’s handwritten caption, “AN ANCIENT VICTIM.”

Based off several operative reports found in the Vault, we now know that Ola Smith “coached” Dempsey to act this way in front of the cameras.

eviction day

Another evicted family of strikers stands in front of their house with their belongings piled high.

the factory’s “thugs”

In her scrapbook, Ola Smith labeled the two unidentified men at center as “company thugs.” These men oversaw the evictions and attempted to block Smith’s camera on several occasions.

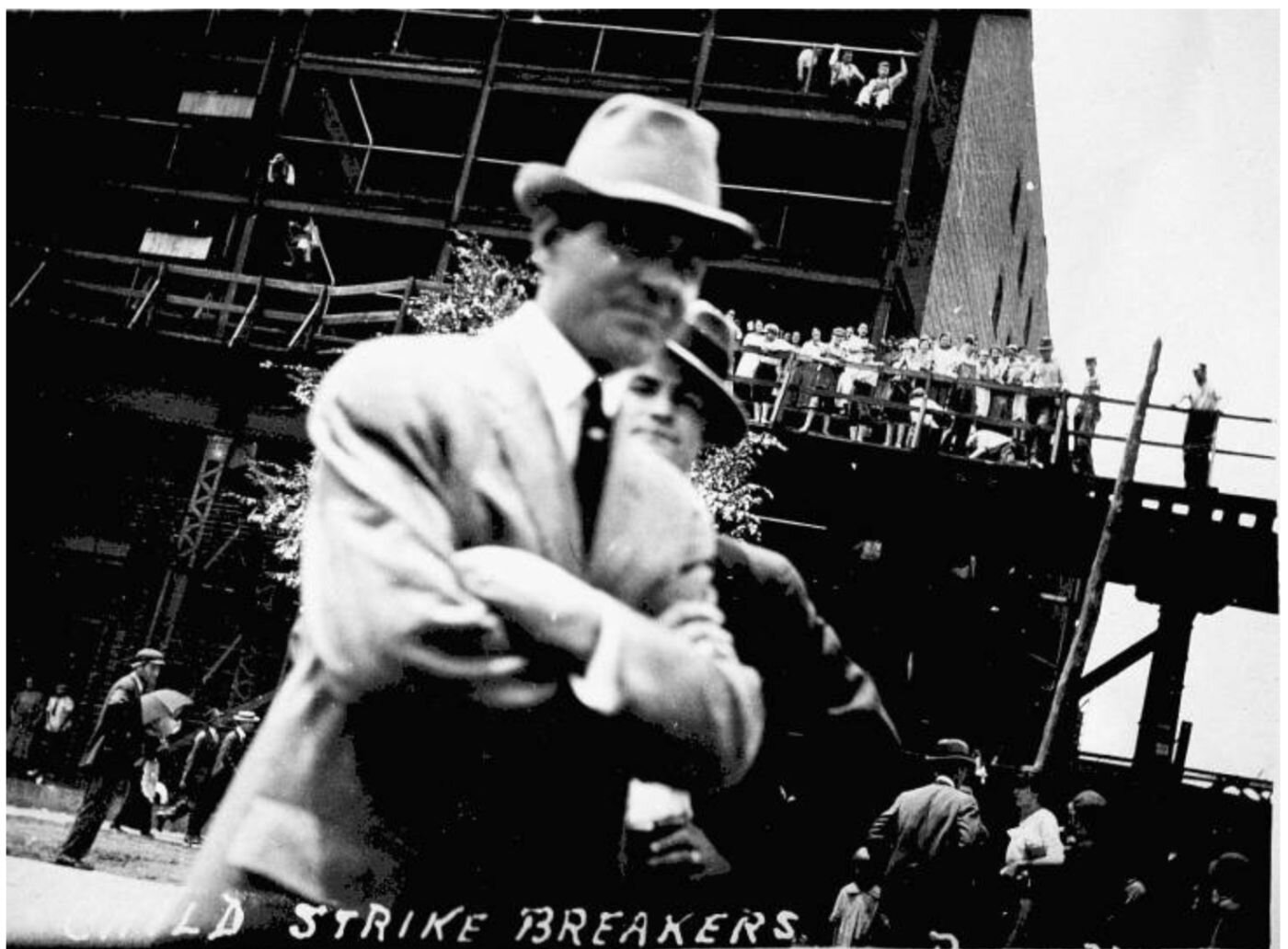

“child strike breakers”

Two factory men attempt to block Ola Smith from taking photos. A group of workers look on in the background.

blocking ola

Another man attempts to block Ola’s camera.

Her caption reads, “‘Spotted a Spotter’—just after he endeavored to knock the Kodac from my hand. ‘The back of Shields’—’Chief Special agent’ for the mill.”

“put out by the mill owner”

Ola Smith took this photo of a forlorn, homeless striking family. She was also likely responsible for creating the sign shown in the photo.

eviction day drama

A dramatic caption, written in Ola Smith’s signature style: “With curling lips, the Company’s watch dogs made fun—as the misery increased.”

a threat to burdett

As the strike dragged on into June, strikers began pressuring more and more non-strikers to join their cause. This was one hand-written threat sent to Walter Burdett and eventually submitted to Oscar Elsas. On the envelope, a note was made that “This letter was found under this boy’s door this A.M.”

a threat to mrs. hardman

A threatening letter sent to a Mrs. Hardman whose sons worked in the mill.

“WE AR GOIN TO STOP IT IF WE HAV TO USE FORC TAK WARNIN.”

“…and all of his son of a bitch pimps.”

When Oscar would hear stories of threatening behavior from strikers, he would often have them tell their stories and then certify them with a sworn affidavit.

In this affidavit, non-striker Otis. A. Thomason swears he heard a striker on Carroll Street say that he “would like to see the time come around, when I could help to kill Oscar Elsas & all of his son of a bitch pimps.”

“dynamite the mill”

In this affidavit from June of 1914, Miss Claudia Fuller states that a striker claimed that, unless the rest of them walked off the job, a group of strikers would “dynamite the mill.”

“let us have justice”

On June 3, 1914, Atlantans awoke to this bulletin from the Men and Religion Forward Movement, printed in the Atlanta Constitution.

The Men & Religion Forward Movement was a loosely organized group of evangelical ministers and protestant businessmen that used their faith to war against moral decay and advocate for social causes. It was a major PR coup for the union when the MRFM came out in support of their cause. This was the first of several bi-weekly bulletins that appeared in papers throughout the summer of 1914.

“capital, labor, christ”

At left: Exterior of the Grand Opera House

At right: Interior of the Grand Opera House

On June 28, 2,000 people packed into downtown Atlanta’s Grand Opera House for a rally hosted by the Men & Religion Forward Movement. Several leaders of the MRFM spoke, railing against both the vices of the day and the management of the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill. The meeting ended with a resolution, calling on Oscar Elsas to enter into third-party arbitration talks with the strikers.

INTERESTING FACTS: The Grand Opera House was originally built with funds donated by Fulton Bag founder, Jacob Elsas. In 1939, it hosted the premiere of Gone with the Wind. And in 1978 it burned and was eventually demolished.

To see photos of the structure before it was demolished, click here.

elsas responds

Just two days after the rally at the Grand Opera House, Oscar Elsas issued this statement to all three of Atlanta’s major newspapers.